We have accumulated enough knowledge about the protection of biodiversity. Now it has to be implemented urgently – also with the help of rangers. That’s what zoologist Cornelia Krug and ecosystem resilience researcher Mats Nieberg say. Both contributed to the recently published study “10 Must Knows from Biodiversity Science“.

The new edition of the international study by the Leibniz Research Network on Biodiversity is a summary of the most important fields of action for stopping the current mass extinction. In this study, Krug analysed the area of international cooperation focusing on education for sustainable development (Must Know 8) and Nieberg examined how to reconcile the use of forest ecosystems and biodiversity conservation (Must Know 5).

In our interview, Krug, working at Zurich University in the research focus area Global Change and Biodiversity, and Nieberg, doctoral researcher on the resilience of forests and ecosystems at Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, talk about their findings and the central role of rangers.

The findings on undiscovered biodiversity were particularly eye-opening for me. It is of crucial importance and we can only preserve it by focussing on ecosystems as a whole.

Mats Nieberg, researcher at Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research © Rosa Castañeda

What findings in the current study are particularly striking for you – across all 10 must-knows?

Cornelia Krug: The urgency: it is not long until 2030, the horizon for the global biodiversity targets of 2022. And this year also marks the end of the implementation period for the UN Sustainable Development Goals. So we really need to act now. We have focussed particularly clearly on consumption. In the chapters on agriculture and forestry, for example, we have made it very clear that biodiversity protection must be taken into account here in particular.

Mats Nieberg: The findings on undiscovered biodiversity in Must Know 3 were particularly eye-opening for me. The biodiversity that we have not yet discovered plays a crucial role. We cannot preserve it through targeted species protection or the protection of individual habitats, but only by focussing on the ecosystems themselves. The fact that the soil harbours more than half of all species was very surprising to me.

I was also enlightened by the findings from Must Know 1, according to which climate and biodiversity protection should be considered and implemented together. After all, there are many measures that can help protect biodiversity and tackle the climate crisis if they are designed with a “biodiversity lens”.

2030 is close, the horizon for the global biodiversity targets of 2022 and the end of the implementation period for the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. We really need to act now.

Cornelia Krug, researcher for Global Change and Biodiversity at University of Zurich

What do you think is the biggest difference compared to the 2022 Must Knows?

Nieberg: In my view, the biggest difference is a stronger focus on proposed solutions. We have tried even harder to formulate recommendations based on existing research that are relevant for decision-makers at various levels.

Krug: I also find the clear focus on options for action in 2024 the most striking. We have the knowledge of biodiversity research, but there is a problem with implementation. That’s why we need to prioritise biodiversity conservation issues. We have the Natural Climate Protection Action Programme in Germany and the EU Nature Restoration Law programme. These are policy instruments that need to be implemented as quickly as possible – despite all the conflicts we are currently seeing in the massive protests by farmers in many countries. We must join forces with them to see how their negative impact on biodiversity can be minimised and how they can benefit from it.

Are there any findings that have particularly surprised you in the course of researching your subject area?

Krug: What is really developing is the collaboration between art, science and the public. There are more and more citizen science projects as a direct link between science and society. And art is working together with science to develop concepts that focus not just on information but also on emotions. This allows people to be involved in biodiversity in a completely different way. For example, the Artists in Lab programme in Switzerland or the large international project Fungi Cosmology, which makes the role of fungi for the ecosystem and for humans visible.

Nieberg: For me, it wasn’t so much the findings that made it into the Must Know 5 on forests that were striking, but the lack of knowledge. For example, it was particularly difficult to find reliable knowledge about the actual effects if we designate more protected areas in the German forest and continue to use the remaining forest as a supplier of raw materials and for other ecosystem services. Is the pressure on biodiversity shifting abroad? Or are there clever solutions so that there is a net gain for biodiversity globally?

Who do you see as the key players in the transformation?

Nieberg: Decision-makers at all levels whose decisions have an impact on the forest are important. These are politicians and forest managers in particular, but also anyone involved in environmental education. And researchers need to be in dialogue with practitioners in order to identify and, if necessary, close information gaps.

Wherever ecosystems are to be protected, we must involve indigenous and local populations. They have important knowledge about these ecosystems they have lived with for generations.

Cornelia Krug, researcher for Global Change and Biodiversity at University of Zurich

Krug: In general, we need to bring the various professional groups together, whether teachers, rangers, biodiversity researchers or urban planners. It is important that biodiversity research goes into schools. Nature education is usually neglected there. Teacher training is also needed here to equip teachers with new skills to teach pupils more than just facts about nature and biodiversity. Rangers already play an extremely important role here for the population: in imparting knowledge, but also their personal relationship with nature and emotions. Investors are another big player. In their daily decisions, they have a huge influence on biodiversity. In order to demonstrate these effects in terms of the best possible nature conservation with suitable indicators, close cooperation with biodiversity science is also required here.

How can the work of rangers for the preservation of biodiversity also have an impact far beyond the protected areas?

Krug: Rangers create a connection between people and nature, they interact with visitors and convey what is special and worth protecting. If they take people into their area and let them experience the special smells, sounds and emotions, they can win them over to the cause of nature on a deeper level. This has a multiplier effect because people pass on what they have understood on an emotional level: how important nature conservation is, even outside the protected areas. Indigenous and local population groups have a completely different approach to nature and its diversity. We need them, also as rangers. Because they have a great deal of knowledge about the ecosystems in and with which they have lived for generations. We need to enter into a good dialogue with them and involve them wherever the protection of these ecosystems is concerned. If this is successful, it is much easier to establish contact with the wider population on an equal footing, for example when designating new protected areas.

Rangers can create emotional experiences with a knowledge transfer component to put natural processes into context. This has immense potential for impact outside of protected areas.

Mats Nieberg, researcher at Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research

Nieberg: The rangers have the valuable opportunity to talk about nature and species conservation while they are out in nature. Emotional experiences in protected areas with a knowledge transfer component that puts processes and developments, such as dead forest areas, into context has immense potential for an impact outside the protected areas as well. Targeting decision-makers at various levels could be the key to success.

In your opinion, what are the most necessary steps that the international community must take next to stop the current mass extinction?

Nieberg: The biodiversity crisis – just like the climate crisis – should be recognised as a potentially existential threat to our societies. Aligning all policy measures with the goals of the Global Biodiversity Framework can be a first step.

Krug: The most important thing is to protect what remains. That is a matter for politicians. And the existing laws must be implemented by the authorities. I also believe that taking responsibility is very important: the ecological footprint we have in Europe is relatively small. This is because we are not primarily destroying our domestic nature, but that of other regions of the world. At the same time, however, we are passing on responsibility for protecting the remaining nature there to the developing countries. Instead, we must support them in this and in their development. It is up to each and every one of us to consider how we can drive the transformation forward together. In doing so, we will have to make sacrifices for our future viability. But we must understand what we gain. Taking meat consumption as an example, health, animal welfare and more natural habitats instead of farmland for animal feed.

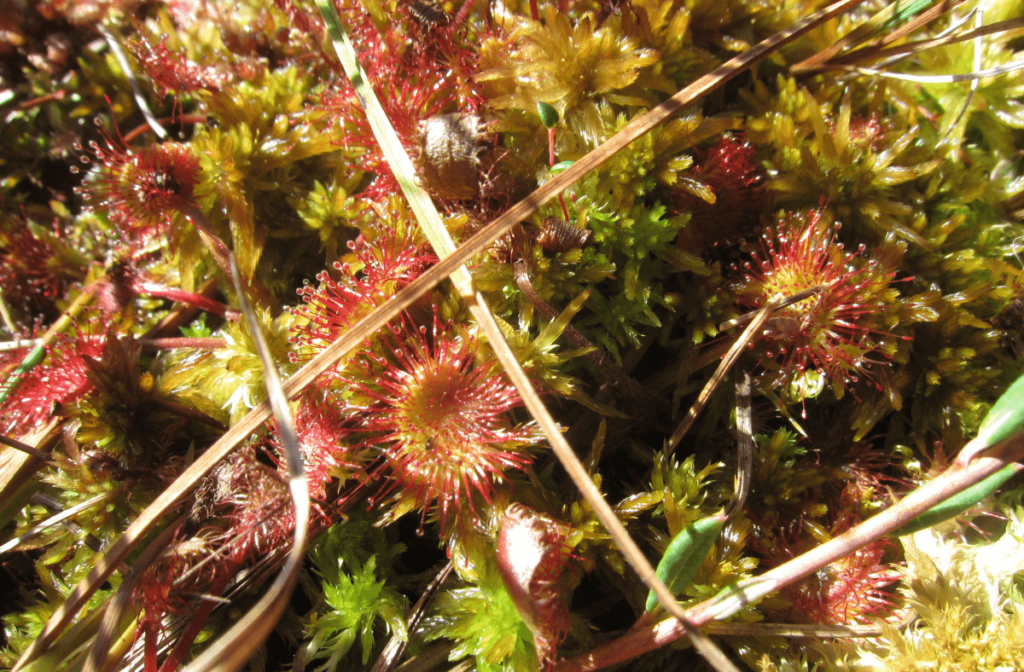

Header photo: Nature communication training for rangers in Denmark

editorial work for this

content is supported by