If you ask Armando Di Marino about his working life, he says that he never worked – that’s how little his four decades as a ranger were a job and how much of a passion they were for him! Yet he has invested a great deal in raising awareness of the immeasurable value of nature, especially in the most important ranger job for him: environmental education. Here he talks about his techniques and uses his great expertise to give tips for other rangers in environmental education.

Armando, how did you become a ranger?

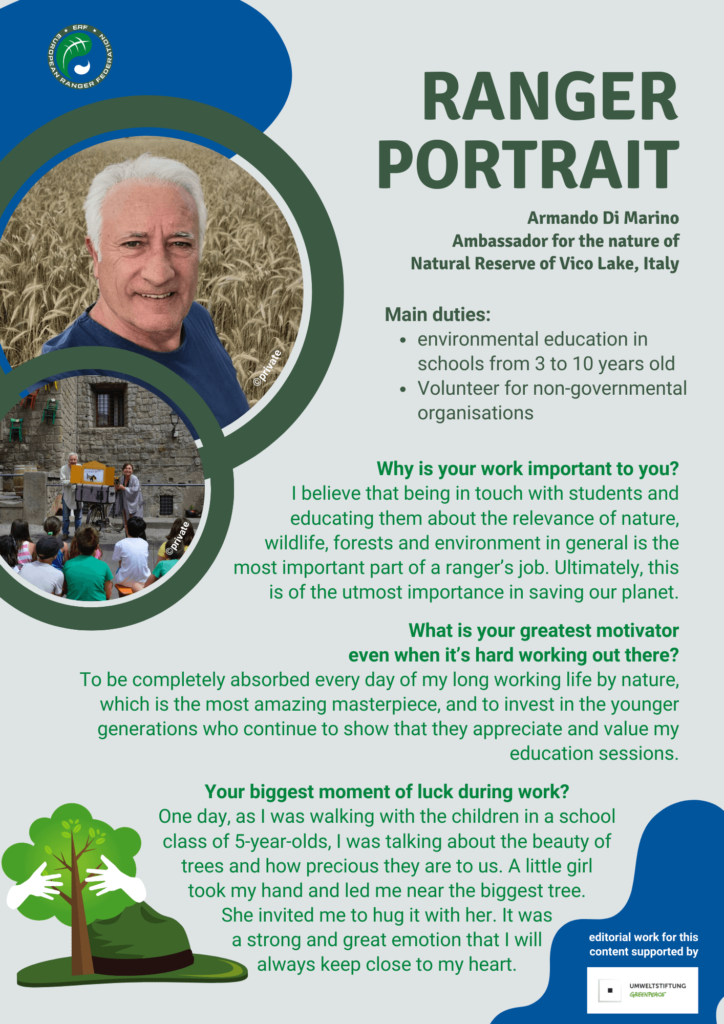

I was 27 years old when I applied for an open competition for Rangers. One of the topics of the competition was photography, which I have always loved. I won the competition and was hired. I worked for about 40 years as a ranger in the Lake Vico Nature Reserve, a protected area in central Italy that was established in 1982.

What were your goals as a ranger?

My overall goal was to protect nature and encourage everyone to discover the beauty of the natural world. In Italy, the ranger is employed by the state like a police officer. Rangers take action against criminal offences such as poaching, illegal fishing, illegal building projects or illegal logging. The ranger is also responsible for tasks such as monitoring and protecting animals and plants, rescuing wild animals, scientific research and civil defence.

How did you get into environmental education?

I have understood that we can only change people’s behaviour if we make them understand that nature must be respected. To develop environmental awareness and reduce our ecological footprint, we need to start with the younger generations! That’s why I met pupils aged 3 to 10 to share my experiences and talk about wild nature. I have invested a lot in reaching out to the children in the best possible way and maximising their opportunities to learn about nature. In the end, environmental education became the most important part of my work. And I believe that being in touch with students and teaching them the importance of loving nature, wildlife, the forest and the whole world that harbours us is the most important part of a ranger’s job. Ultimately, this is of the utmost importance for saving our planet.

How did you train to teach the youngs about nature and which techniques worked best?

I have attended many courses and developed techniques to get students actively involved. The best technique is to let them have fun or go for walks in nature, which sparks emotions and sensations. To keep the students engaged and interested, I have adopted an ancient but very effective communication technique called Kamishibai! This is a Japanese communication art that was used by storytellers in the last century. Kamishibai means paper theatre.

“Using the Japanese storytelling technique Kamishibai,

I invented stories of nature to speak to the heart of the students.”

The storyteller travelled around the country with a small wooden theatre installed on a bicycle. Inside the theatre were some pictures that the storyteller ran through like a PowerPoint presentation, entertaining the children. Using this technique, I invented some stories myself to speak to the hearts of the students.

How does this art of storytelling for environmental education still accompany you today?

I retired a year ago and continue to be an ambassador for the nature park to raise awareness among students. I also volunteer for non-governmental organisations such as Legambiente and Lipu, which work to protect the environment and wild birds.

“It’s a real pleasure to let people discover the secrets of nature

through the song of the birds, the rustle of the leaves, the smell of the soil.”

I still often take schoolchildren and people with disabilities through the woods; it’s a real pleasure to let them discover the secrets of nature through the song of the birds, the rustle of the leaves, the smell of the soil. We have a lot of fun and build trusting relationships at the same time. I have always done my job with love and put a lot of energy into passing on my knowledge and experience to the younger generation. I think I have been sowing all these years and some seeds are growing.

What are the results you have observed from environmental education?

Sometimes I meet people who tell me: “Hello Armando, I still remember well how we used to go for walks in the forest and how you told us many stories about nature, let us play many games and taught us many secrets of nature. Many of those children are now vets, agronomists, forestry workers and biologists. That gives me meaning to my life.

Can you remember a key moment when you really felt that the message had got through?

I remember a call from a policewoman who asked me for help. She had found an injured animal, a porcupine. When I arrived, I learnt that she had taken part in a project for young rangers in which she was enthusiastic about nature.

What tips do you have for rangers who do environmental education?

You have to combine environmental education with awakening strong emotions and fun, as opposed to the traditional educational approach in schools. It really pays to put as much enthusiasm as possible into educational activities. In addition, I think training and sharing experiences among rangers is very important.

“Discussing the different techniques and opinions on environmental education

with other rangers from different countries can broaden your own knowledge.”

By discussing the different techniques and opinions on environmental education with other rangers from different countries, you can broaden your own knowledge. So take part in international ranger meetings whenever you can! I attend international ranger conferences such as those organised by the International Ranger Federation almost every year to share knowledge and the spirit of belonging to the international ranger community.

What conditions for environmental education by rangers would you like to see in future?

Firstly, I would like to see an end to all wars. Apart from the immeasurable human suffering, wars have a severe and terrible impact on nature. Secondly, it is necessary to continue environmental education in schools and public institutions with greater involvement of teachers. They are the first to be trained in environmental education. Rangers can visit schools several times a year, but that is not enough. Environmental education must take place on a daily basis.

© all photos by Armando Di Marino – winner of our Volunteer Photo Competition; header photo: introducing boy scouts to the Lake Vico Nature Reserve

editorial work for this

content is supported by